Surviving the Tallest Mountain in the Contiguous US: A Tale of Friendship, Altitude Sickness, and Piss

August 11th, 2019

Part 1: Introduction

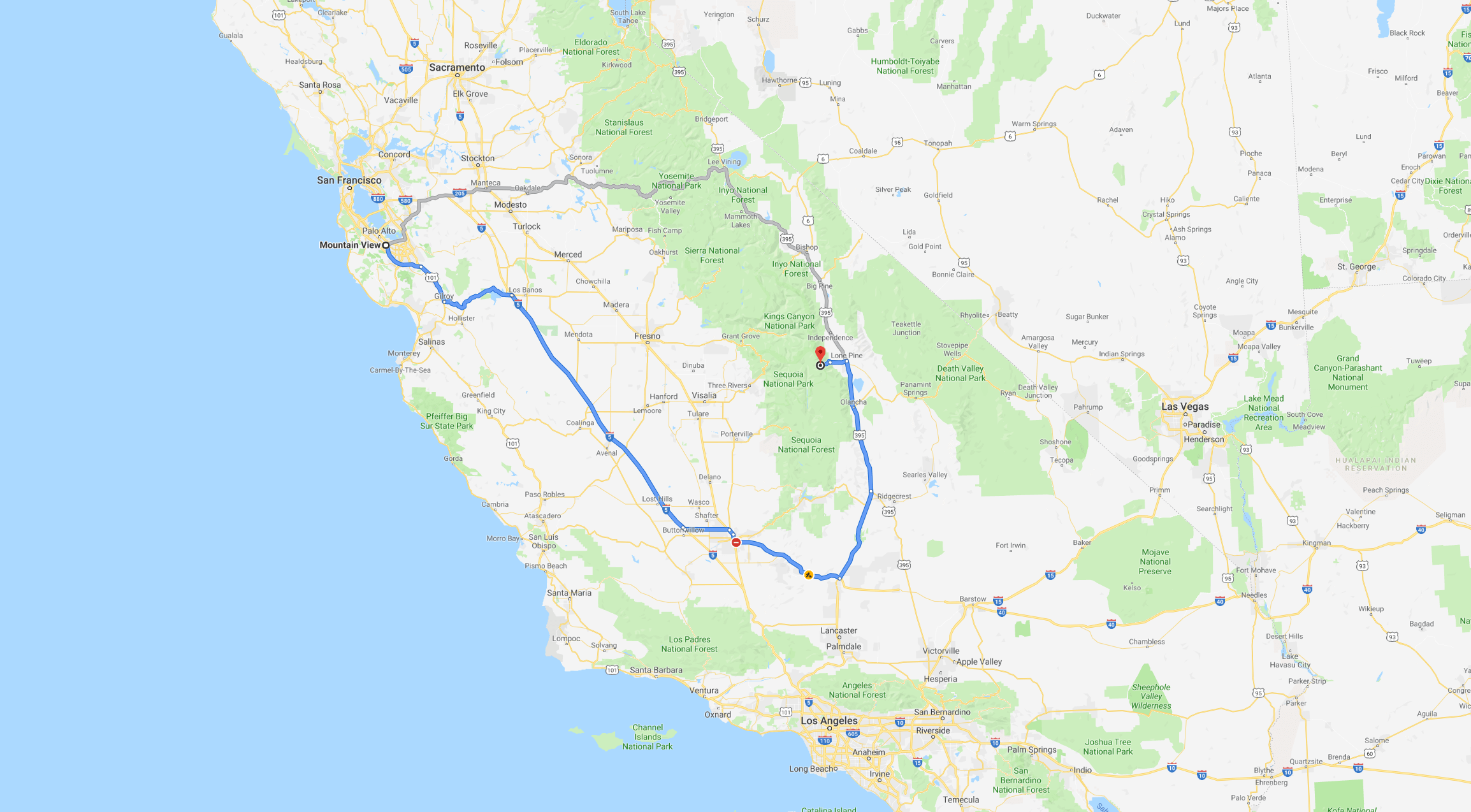

On August 6th, 2019, Douglas Qian, Newton Xie, Noriyuki Kojimano and I set out from Mountain View, CA to tackle Mount Whitney.

Not only were we determined to summit the tallest mountain in the contiguous United States, but to also do it in one day. In comparison, most overnight backpackers take between 2 and 4 days to complete.*

Once upon a time, my lack of preparedness put me through bouts of suffering on Mount Fuji, so this time around I made sure to be extra cautious. Our journey is detailed below. See here for my complete packing list.

Part 2: Acclimatization at Lone Pine Lake

Reading about altitude sickness and high-altitude cerebral edema which could permanently damage your brain and lead to death terrified the hell out of us. Soon after getting to Lone Pine, acclimating by resting at a higher altitude for a while seemed like a good idea.

So we hiked the 5.2-mile loop to the lake. We stayed at the lake for a couple of hours to help with the acclimatization.

During the ascent, we heard thunder and saw lightning from many directions. We were afraid our summit day plans would be jeopardized. Besides the effects of altitude sickness, the most dangerous thing that could happen in this area is being struck by lightning.

A few years ago, this following story headlined the news,

LONE PINE, Calif. — As lightning lacerated the darkening sky over Mt. Whitney and thunderclaps started a deafening roll, the 13 hikers saw the old stone hut with its corrugated metal roof as a welcome refuge from the drenching downpour.

It nearly became their tomb.

“I was sitting on the floor, my back against one of the walls,” said Edward (E.J.) Wueherer, a hiker from Tehachapi. “All of a sudden I saw this flash and I felt this jolt like on my funny bone, and my toe started burning.

“The next thing I knew I was helping to untangle bodies.”

The surging electrical charge threw Matthew Edward Nordbrock, who had been seated in the center of the hut, several feet, where he lay still on the ground.

As the hikers had sprinted for cover during the squall Saturday afternoon, Nordbrock, 26, of Huntington Beach, told one of his hiking buddies: “I’ve been hit by lightning before, so I won’t get struck.”

He died several hours later, after being removed from the 14,495-foot summit by helicopter.

We drove back to our Airbnb in Lone Pine shortly afterwards.

Part 3: The Big Day

We went to bed around 8:00 p.m. that night and set our alarms for 2 a.m., but too anxious to start the climb, we naturally woke up around 1:00 a.m. We arrived at the Mount Whitney trailhead around 2:00 a.m.

For a few hours, we navigated the mountain trail by relying completely on our trusty headlamps. We strained our ears for signs of a thunderstorm which would've stopped our hike cold and saddened us deeply.

There were a couple of streams that we had to cross, but they were quite manageable and my feet were never wet beyond my toes. We scheduled periodic snack breaks every 1.5 hours and took breaks and filtered water as needed.

After a few hours of hiking in complete darkness, we began to see the faint glow of the rising sun. Our hearts shrank as we saw the dark clouds in the distance. There were few people on the trail and was it felt unnaturally quiet as there was no wildlife. At that moment, I felt like we were the only living things alive in the world.

"The sky looks clear!" I shouted in relief as I realized that the clouds we saw earlier were just mountains.

We continued to set our hopes high, but also kept our expectations low to avoid potential disappointment.

We saw a lot more people as we neared the trail camp. Unlike us knuckleheads, most sane people take on this mountain in many days. We enviously watched as groups of well-rested, fully acclimated backpackers packed up their tents, prepared warm breakfasts, and readied themselves to tackle the summit.

This was the last place to get water according to both online and local sources. One person told us that we only needed to bring 1.5L to 2L of water–which we realized didn't make sense only after it was too late.

2 liters of water got me to trail camp and the route to trail camp was only a quarter of the entire trail. From trail camp to summit and back to trail camp was around half of the entire trail, so at the very least we should have brought 4L of water.

This also marked the beginning of the infamous "97-switchbacks".

Still more than a half-hour from the summit and more than five miles to our next water source, Doug realized he was out of water. Hiking without water at such an altitude was a recipe for disaster.

My summer at Microsoft taught me a great deal about "growth mindset" and trying new things, so I half-jokingly suggested, "Hey guys, let's just drink our piss!" We had filters anyways.

I didn't expect them to take me seriously, but Newton was actually like, "Sure."

And so, Newton, being the next to piss, pissed into one of our filter bottles.

Not yet ready to become Bear Grylls, Doug responded, "Hell no!" when offered the piss-filtered water. Newton, being a true friend, offered the rest of the water from his bottle to Doug and drank the filtered piss himself.

When asked what the water tasted like, Newton though for a second, furrowed his brows and said, "It didn't taste like water. It tasted a bit bitter."

Who knew?

(So apparently, drinking filtered piss is actually a terrible idea. See this comment thread for details.)

Oh and Doug never ended up taking the water that Newton offered him, so Newton drank the filtered piss for no reason.

It was around this point that acute mountain sickness began to seriously impact our performance. Even with the two previous days of acclimatization, Nori's heartrate remained a steady 180 BPM, Newton felt nauseous, and we all had the worst headaches of our entire lives.

Every few minutes, I felt my head throbbing and pulsating with blood.

Step.

Throb.

Step.

On the outside, my face was deadpan, but internally I was screaming.

If it had gotten much worse for us, we would've turned back for safety reasons, but since the swelling of blood of my head would reside after a few minutes at a certain altitude, and it was tolerable for Newton and Nori we continued onwards.

While we were all suffering, Doug, on the other hand, luckily experienced no symptoms whatsoever. Apparently 40% of mountaineers don't experience AMS symptoms at 14,000 feet. Why? Nobody knows.

There was no way that we would come this far to turn back now. Giving up was not an option. Even though we were all in pain, Doug and I kept yelling words of encouragement such as "We got this!" and "We're almost there!"

Confronting the altitude sickness, harsh winds, and the near-zero temperatures, we trudged onward and eventually made it to the summit.

"YEEEAAAAA" I yelled with the little energy I had left.

We had finally made it to the summit. To celebrate, Doug and I had some refreshing beers. In hindsight, consuming alcohol at the summit might not have been the smartest idea as it slows down the acclimatization process and dehydrates you, but YOLO.

A few pictures in, Nori mentioned to us, "I don't feel good."

Doug and I didn't take this as seriously as we should have. His tone didn't sound urgent to us and we wanted to take as many pictures as we could. Doug showed little symptoms of altitude sickness and my painful headache was quickly fading.

A couple minutes later, Nori said, this time more seriously, "Hey guys, can we head down soon?"

By that point, we should have noticed that something was up, but we continued chatting with other hikers and went about our own business.

A few more minutes passed and this time Nori interjected our conversation and sternly demanded, "We need to go down. NOW."

Only this time it hit us how urgent this situation was and I told Nori to immediately head down first, with Newton accompanying him. Only later did Nori tell us how much discomfort he was in. This event made me realize how subjective our experiences are and why it matters so much to be open to the subtle hints that other people give you. This could've turned out badly and I'm so glad it didn't. Some extra few pictures aren't worth the suffering of a fellow pal.

On the way down, Doug and I thankfully found a few sources of water that we could filter on the way down so that we didn't have to drink more piss.

The summit is only halfway. Descending wasn't easy until we got a second wind when some hikers told us about the best burger ever at the Whitney Portal Store. Picturing fat juicy burgers in our heads, we immediately began running down the mountain to make it to the store before it closed.

Doug wanted the burger so bad that he was willing to further damage his already painful knee to take a bite of the delicious burger.

To get the burgers before the store closed, Netwon offered to stay with Doug while he asked Nori and me to run down the remaining 5 miles of the mountain trail to get the burgers. We made it down in record time.

What better motivation than food?

In total, the hike took just under 16 hours. What a day.

Was it worth it?

Definitely.

This hike may be the hardest non-technical day-hike in the contiguous US. (Technical hikes require the use of hands, usually involving mountaineering equipment such as ice axes and crampons.) At the very least, it's the tallest. The hike wasn't technical at all. I remember only having to use my hands twice, when there were icy rocks on the switchbacks and when I slipped coming down on the snowfield.

Though it was a long hike, anyone who is somewhat athletic and has good cardiovascular health should be able to conquer this mountain. Training will vary from person to person. A few months before this, I trained for a marathon at a 3:30 to 4:00 pace and I did a 10+ mile trek in Washington state. I also did some targeted work on my calves, side glutes, and hip flexors because of some muscle imbalances. Besides having also trained for and ran a marathon a few months prior, Doug didn't do any extra training for the hike and was also fine.

The hardest part of the hike was the symptoms of altitude sickness. Only Advil made the altitude sickness bearable.

We were barely sore the next day. "Round two, anybody?" joked Nori.

What's next?

There are two routes I can take. I can either stick with non-technical hikes and start doing multi-day hikes, or I can start doing technical hikes.

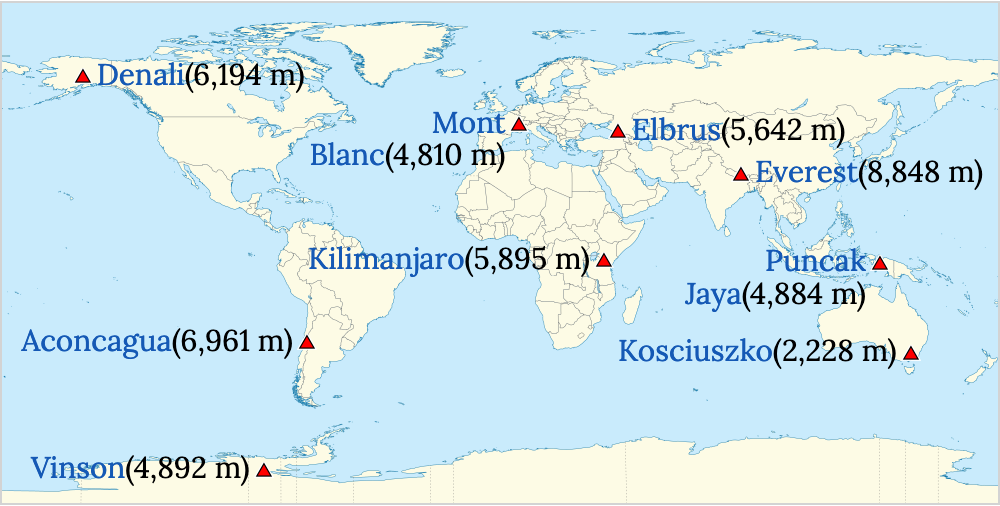

More challenging non-technical hikes include Mount Kilimanjaro (19,341 ft / 5,895 m) in Tanzania, Africa or Mount Aconcagua (22,837 ft / 6,960 m) in Argentina, South America. Both of these are part of the Seven Summits, which are now on my radar.

Or, I could start learning technical mountaineering skills such as self-arrest with an ice ax and begin to do technical climbs such as on Mount Rainier (14,111 ft / 4,392 m).

Whichever I choose, this hike has done a poor job at deterring me from more challenging hikes and only has me craving more.

My Complete Packing List*

Besides the beer, bring all the following and only the following. Avoid any non-essentials not listed to reduce weight. This packing list is only for the day-hikers. Multi-day summits will need extra gear such as a tent, sleeping bag, etc.

- Moisture-Wicking T-shirt

- Pants (Prana Stretch Zion Straight Pants)*

- Socks (Darn Tough Hiker No-Show Light Cushion Socks)

- Shoes (Altra Lone Peak 4 Trail-Running Shoes)

- Hiking Poles (Black Diamond Carbon FLZ Trekking Poles)

- ~20L Backpack (Osprey Talon 22 Pack)

- Mount Whitney Permit

- Windbreaker

- Rain Jacket

- Synthetic Down Jacket

- Fleece Jacket

- Extra pair of socks

- Hat

- Sunglasses

- 1.5L of Water, 3L Total Capacity**

- 1500+ Calories of Food – You will burn over 4000 calories on this trip!

- Beer***

- First Aid Kit (Adventure Medical Kits Ultralight/Watertight .3 Medical Kit)

- Water Filter (Katadyn BeFree Collapsible Water Filter Bottle 1L)

- Pocket Knife (Victorinox Hiker Swiss Army Knife)

- Lip Balm with SPF

- Sunscreen

- WAGbag – The anywhere toilet kit****

- Map****

*My recommendations are in parentheses.

**The amount of water you bring depends on the the time of year and the water conditions. Check with the park ranger or with recent hikers through AllTrails or the Mt. Whitney Facebook Group to see how much water you should be bring.

*** Bring and drink at your own risk.

****You will be given one of these for each person in your group when you pick up your permit.

If you have any questions or need any tips about the hike, feel free to reach out!

Lastly, do your own research and take everything with a grain of salt. Personal experiences are very subjective. If you want to summit Mount Whitney, start preparing before February of that year as the permit lottery applications are due during that time. The hardest part may actually be getting a permit since the acceptance rate is around 30%. Overnight permits are even harder to get. See Mount Whitney via Mount Whitney Trail on AllTrails for more information about the trail.